Blog posts from seminar 2

Neighbourhood Plans and Co-Production: Still Some way to Go

Dr Sue Brownill, Department of Planning, Oxford Brookes University

Standing in the shadow of the new Francis Crick Institute listening to Michael Parkes, community planner, and Donna Turnbull who works for Voluntary Action Camden talking about the emerging Somers Town Neighbourhood Plan, some of the key questions this seminar series is addressing became very clear.

We saw first-hand the pressures facing this low-income community nestling between Kings Cross and Euston stations from property investment and gentrification and from austerity urbanism as the council’s Community Investment Programme redevelops public assets. We also heard about the passion, the efforts and the collaborations that the community have harnessed to prepare their plan. So can neighbourhood plans ensure community needs are met, what knowledge and ways of knowing are needed to achieve this and how can communities, universities and others work together to generate this knowledge? In short, is the co-production of plans possible?

The term co-production has emerged to describe and set out a goal for the coming together of policy makers and communities to jointly develop and deliver services. It means pooling knowledge, ideas and resources to come up with solutions and empower communities. As the New Economics Foundation says “where activities are co‐produced in this way, both services and neighbourhoods become far more effective agents of change”. But co-production, as Yasminah Beebeejaun rightly reminded us in her presentation, is about the transformation of planning and other practices, not just working together. The workshops, discussions and presentations throughout the day provided many insights into the extent to which neighbourhood planning can really be seen as such a transformatory initiative.

On the one hand we heard about some of the positive aspects of the coming together of different interests to generate knowledge in neighbourhood planning. Michael spoke about how the community had organised input from universities and others on issues such as housing, planning gain, community assets and environmental assessment to help the community develop their plan policies. The day itself followed through this spirit by bringing together academics, consultants, local planners and others involved in neighbourhood plans in workshops on the key issues currently facing the Somers Town Plan (housing, influencing planning decisions and community assets) to take these further and to share ideas and knowledge from different areas. Andy Inch and Elena Besussi talked about their work bringing students and neighbourhoods together, trying to change planning knowledge from within by involving tomorrow’s planners in neighbourhood working as well as producing evidence, reports and information for community use. Robert Rutherfoord from DCLG commented that ‘people wouldn’t be talking as much as they are about planning without neighbourhood plans’ implying that planning knowledge is becoming more widespread through the process. Joint working means a constant dialogue which challenges understandings; as I for one found in the discussions with community representatives about the aims and organisation of the day (the errors are all mine).

But we also heard about some of the limitations and challenges of working together. Andy Inch spoke of the ‘ambiguous role of the engaged university’ ; looking to promote its community profile and attract students while also supporting communities and about how academics should not forget that ‘we are the hard to reach’. Elena Besussi raised some equally important points about the ethics of students and community groups working together (which are also discussed by Andy Yuille in his blog (see below) and the need for guidelines such as those promoted through the Just Space protocol which recognise the power dynamics involved. She also asked whether universities can or should be expected to fill the knowledge gaps around neighbourhood planning.

So has the knowledge being used in planning been transformed through neighbourhood planning? The fact that communities are finding it necessary to work with academics and consultants in neighbourhood plans, however supportive, would suggest not. Have planning practices been transformed? Simin Davoudi’s telling statement suggesting that the ‘terms of engagement ‘of neighbourhood planning are not the right ones to fully involve and empower communities also suggests not yet. And our discussions raised questions about whether neighbourhood plans are imposing a rigid structure on fluid communities and ‘risk turning community groups into planning departments’ rather than turning planning into a community-focused practice .

Finally, there is another major question raised by the Somers Town experience; is the neighbourhood knowledge generated through the NDP process and through working together enough? Michael Parkes spoke eloquently about how the aim of the plan is to enable the community to stay and to get a slice of the action through being able to extract some of the uplift in values through regeneration for community benefit. But whether or not the knowledge now embedded in the NDP will be able to mediate the processes impacting on Somers Town, many of which have their origins outside the area, remains to be seen. Equally elusive is the wholescale transformation of planning knowledge and practice which would enable neighbourhood planning to truly bear the label co-production. The day showed that there is a real appetite for working together, that we have come some important steps along the way but it is a journey that is not yet over.

Co-producing Neighbourhood Planning: A Perspective from Leeds.

@will_sparling

PhD candidate at Leeds Beckett University

Introduction

Co-production of a Neighbourhood Plan is possible, but is there enough to gain? Working together on a Neighbourhood Plan is just one example of where co-production in the planning system might be used (David Farnsworth has written on the use of mixed development forums at a variety of scales, for example). And it is, in my view, one of the toughest, for three primary reasons that might be shared equally between researchers, practitioners and residents. Equally, Neighbourhood Planning has been brought into law, and so there is plenty of scope for being positive about what can be achieved.

Given the title of seminar two – Sharing ideas and knowledge for Neighbourhood Planning: is co-production possible? I’d like to share a little of my story from Neighbourhood Planning in Leeds. For clarity, Neighbourhood Plan[ning] and Localism as enacted by the previous Coalition Government (2010-15) and continues, will always be capitalised to distance it from other concepts of neighbourhood and localism.

Firstly, it is an infant, which makes it difficult in itself. In British planning, Localism in this format remains an emerging and new idea. Secondly, Neighbourhood Plans become a statutory document once made, created as part of an increasingly complex system. The process to create a Plan, thus decisions made against them, are situated somewhere within a profession that may be suffering from an identity crisis because of this. Thirdly, and despite rhetoric, Neighbourhood Plans are limited in their influence and this is confusing. This might sound too negative, or perhaps it represents my feelings of the planning system currently. Moreover my experience is that many people are ready to engage with planning, but it is largely seen as a negative system (even compared to other political eras). The positives are there within Neighbourhood Planning however, and they are ready to be claimed.

Personally I am very lucky to have experienced the Leeds perspective, where there are approximately 40 Plans at various informal and statutory stages. That isn’t to say Neighbourhood Planning in Leeds is the panacea it may be perceived as – and I feel the others involved wouldn’t believe that either – but there is a positive feeling surrounding the concept in the city. Therefore I write from my perspective of being involved in a few ways, as a resident in my village, a PhD researcher investigating two inner-urban case studies, and (less so here) as a paid adviser. Others may have a different take.

The infant

Being a relatively new concept (despite having been around for 3-4 years), Neighbourhood Planning – as Coalition Government (2010-15) deployed Localism – is in its infancy. It still remains a challenge to come to terms with and understand if this is the ‘right type’ of localism. Will it deliver housing in the good places we need? Will they receive enough weight in decision making? Will they achieve certainty for developers? As has been highlighted before in various research papers, there was no Government White Paper to discuss the new legislation which became the Localism Act. As a result this can be considered state deployed localism, created at the national level and established across England.

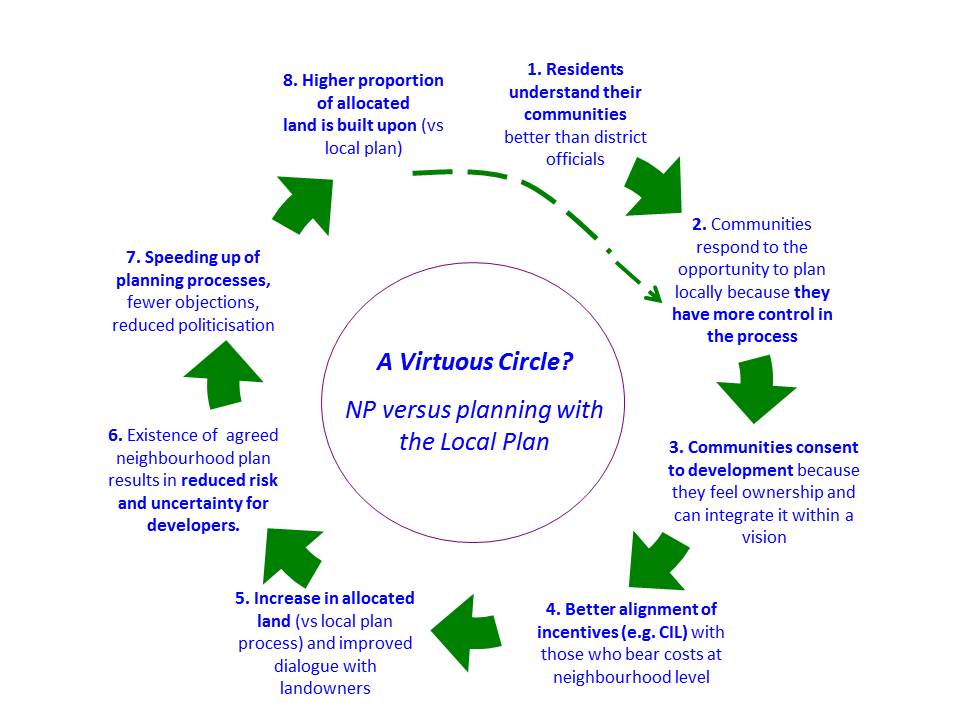

An aim of Neighbourhood Planning is to create certainty for developers, by increasing the amount of land allocated in local authority areas. Some of us may have already seen a diagram of “Neighbourhood Plans vs Local Plans” (below), outlining something which is to be ‘tested’ by Government. This diagram says that more development certainty may be achieved by increasing the incentives (money available for infrastructure through the Community Infrastructure Levy for example). Will this be enough, delivered timely and in the right places?

Source: DCLG Roundtable Presentation by Tom Tolfree (2013)

Rhetoric surrounding Localism uses the language of giving power away, freedoms, flexibilities and a strengthening of society. A question remains over how Neighbourhood Planning will work in practice. When planning decisions are made against Neighbourhood Plans, how much weight will be attached to the policy within them? There are approximately 70 made Neighbourhood Plans nationally, so it remains difficult to see how decisions are being made on a large enough scale.

Why is this important? If true co-production of public services is to work, and especially at the neighbourhood level, a good level of certainty is required. Certainty is required because of the amount of investment (time, money, energy etc..) that goes into making Neighbourhood Plans. As with anything, there needs to be some kind of return on this investment, otherwise people won’t put the effort in. Initial rhetoric, excitement and ultimately take-up of Neighbourhood Planning will tail off. With an added danger that other methods of ‘doing planning’ will be used if they are seen to be more powerful, whether it is lobbying, or objecting to planning applications. Clarity of the power of Neighbourhood Planning, as measured against decision making, will emerge over time. So the question is; how can interest in Neighbourhood Planning be maintained? An answer may be found in encouraging urban areas.

Communication with Neighbourhood Planning groups across Leeds is vital, to give them not only clarity of process, but also some degree of certainty on the way forward. Within the Leeds metropolitan boundary, Neighbourhood Planning is still young, with at least one currently at the pre-submission consultation stage, and one other at examination stage, and these are in parished areas. Despite the experience of all of those involved, ultimately the residents producing the Plans, local authority officers and politicians are all, to some extent, awaiting the examiners report to ‘take stock’ of where they are at. How many changes will be required? How long will it take?

One of the biggest challenges of being involved as a resident making a Plan, is not-knowing if what you are doing is correct. It could be argued that there is no right or wrong way to make a Plan and each one will be different, but ultimately it must meet the basic conditions, as well as other policy and legislation. The trick now will be to communicate this experience back to those residents involved in the individual areas. This should then be followed by all those involved in Neighbourhood Planning in Leeds, with particular emphasis on urban areas who face more complex decisions and are ultimately investment much more time into the process.

Complexity

In urban areas, Neighbourhood Plans may have a large and diverse population, bringing together complex needs and ideas. The process of making a Neighbourhood Plan, in their current format, is governed by a complex mix of policy and guidance, planning legislation, case law, and EU regulations. For me this is one of the most significant challenges for all of those involved in making a Plan. It is designed to deliver growth (a Neighbourhood Plan must be pro-development), and this process is fairly heavily regulated (compared to the way it was promoted during the last parliament). The examination period is the final test of whether a Plan has brought these together effectively and within the required ‘parameters’. Such a process can be the primary source of frustration and difficulty, despite guidance from professional planners (private and public sector). This remains a challenge for everyone.

Identity

Much has also been said recently surrounding the profession of planning, leading to suggestions of an identity crisis, so I won’t dwell on this here. But briefly, combined with current political changes, changes to permitted development rights and a clear emphasis on delivering economic growth, there are now serious questions being asked within and outside the planning profession. Is planning able to take on the complex urban challenges that are being faced? What is it for? Who is it for? How can different areas of the profession work much more closely together? How can planning solve the housing crisis?

My feeling from experiences in Leeds is that this has filtered into the popular conscience, and ultimately those involved in Neighbourhood Planning. There is a great deal of confusion about what planning is for, who we are and what we do. If the profession itself doesn’t know, then what hope does anyone else have? If on one hand Neighbourhood Plans are being supported and on the other permitted development rights are taking away some of their power, for example, then this surely isn’t fair. Even if this is a mixture of political decisions, this may appear baffling to many people getting involved. To me, this is symptomatic of the wider profession of planning and where it finds itself. Planning must communicate its ideas with the wider population more succinctly and clearly.

Understanding impact

Understanding impact is something I really feel planning professionals can use their skills to explain and understand. The impact of Neighbourhood Planning on development decisions is also still emerging. Approximately 70 Neighbourhood Plans are now made, but it is unclear how many decisions have been made using the documents or the impact they have had. To co-produce a Plan requires a certain level of certainty, which is why it has been so positive to speak to those involved locally and nationally, learning from one another. Understanding how the concept of Localism is working at a variety of different scales, nationally, locally and importantly at the neighbourhood scale.

As a resident, it is very difficult to reconcile your ideas with how this translates into a policy with real power and influence. There are other limitations too, whether you are trying to create a plan in a rural area with existing planning controls, urban areas with limited sites for development (and scope for CIL incentives), existing issues of transport infrastructure (not possible unless tied to new development), or those issues considered strategic. I could go on. That is why any sense of ‘de-professionalisation’ of planning should be resisted.

The positives are there to be claimed

The benefits of Neighbourhood Planning are there to be had, for those that wish to invest the time required. Despite the issues arising, from Neighbourhood Planning being so new, complexity, an ‘identity crisis’ within planning, and the gap between rhetoric and practice, these challenges can be overcome. One of the biggest points emerging from my semi-structured interviews is the aspect of time (and I would agree from being part of a steering group). Many of those residents I interviewed all said roughly the same thing; they didn’t realise how long it would take and how much effort was required. However, having greater control of planning decisions in their neighbourhood, amongst many other aspects, was broadly seen as being worth the effort.

In Leeds, the Neighbourhood Plans that are now nearer the end of the process than the beginning are those in outlying, parished areas, with more rural characteristics (despite being only 10-12 miles from the city centre). Whilst they have a formal structure through which to pursue, allowing them to organise a little quicker, the real success will be establishing Neighbourhood Plans in urban areas, the process of which takes a little bit longer.

Urban areas, like parishes and towns, have an opportunity to shape development over a very long period of time, including the type, tenure and design of new development. However, in urban areas it is policy which the area will create and can take ownership for, rather than the traditional method of conservation areas and civic societies for example, which may be city wide. Taking longer to establish a Neighbourhood Forum, get it right, and engage with the wider population of their Neighbourhood Area, will be worthwhile. Relatively speaking, the time in which it takes to establish a forum and area designation, will be minimal in comparison to establishing a Neighbourhood Plan. If Plans are then supported in decision making, it might be that urban areas are brought much closer to the decisions made by parish councils, without the need for a formal council structure.

The process of creating a Neighbourhood Plan in Leeds’ urban areas has also had an impact on the wider governance of the city, in a positive way. Departments of the local authority have been brought together to discuss a way forward at the neighbourhood scale, institutions of sport and residents have signed a memoranda of understanding and have begun working much closer together. A regional development agency idea for New York style ‘highline’ project has been revived. New areas are being assessed to establish conservation areas and appraisals are being created for existing conservation areas. There have been signposted walkways have been funded and created. All of this has taken place by working closely with established ‘stakeholders’, elected councillors and Neighbourhood Forums.

Playing on the emotion of the neighbourhood, to create cities for everyone (to borrow from Jane Jacobs), Neighbourhood Planning is based on the communitarian ‘Open Source Planning’ ideas of the Conservative Party. Co-production of public services isn’t all about what you can see; it is about understanding your city, ward or neighbourhood and making best use of policies that exist. The positives are there to be had, some of them might have to be informal.

Our first blog post from our second seminar event is from Andy Yuille from Lancaster University:

Identities, information and inversions

Andy Yuille, Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University

The afternoon speakers at the Somers Town Neighbourhood Planning seminar raised a set of overlapping issues that I’ve come across in my own work – in the first year of my PhD and almost five months into ethnographic fieldwork with two groups developing neighbourhood plans. I will call all groups developing neighbourhood plans ‘NP groups’ for convenience, whether they are Neighbourhood Forums or Town / Parish Council-led, although I recognise that this may mask significant differences.

Identities

Elena Besussi (Barlett, UCL) talked about the neighbourhood planning process in terms of building and organising knowledge by and for communities, in particular in relation to her project which placed MA students with NP groups to deliver projects for them, leading to the development of new identities for communities and for planners, as well as for NP groups. For example, the community seeing itself and presenting itself as a client, expressing its needs, desires and interests as such to consultants or local authorities, and for planners as advocates, advisers, and technical support to those communities, critically engaging with them, respecting their agendas and helping them to deliver them, whatever they must be. She also raised the risk of identities becoming divisive, depending on the organising principles of neighbourhood groups: if the kind of static structure that surrounds plan-making is imposed onto diverse and fluid communities who it does not fit, it raises the risk that the NP group will engage with the community in the style of a mini-Local Authority planning department, as an alien entity, rather than as a movement emerging from within the community.

In the early stages of my fieldwork I’ve seen this happening, but as ever ‘real life’ is even more complicated. In the NP groups I’ve been working with, I’ve noticed a wide range of identities being constructed, in particular in relation to “the community”. Colin Lorne reminded us during questions that “the community” does not have a fixed, static, homogenous, unified identity. My work suggests that the identity of NP groups, at first glance a much more manageable entity to get a handle on, is similarly complex and shifting.

The NP groups that I’ve been working with adopt a range of different identities which shift and slide almost seamlessly from one to another, in the same meeting and often in the same discussion. There appear to be two main ‘blocks’ of identity in relation to the community – being “a part of” the community, and being “apart from” them. As a part of the community, they represent themselves in three main ways, as:

- Belonging to the community, being an integral part of it and emerging from it, but recognising that there is a lot of heterogeneity within that community and that they are just one element of it – and not always an entirely unified element at that!

- Representing the community – the community, variously represented as unified or diverse at different times, have views, knowledge, values, opinions, desires and preferences, and the NP group represents these, which they can do because they are of the community, they share the lived experience or at least have awareness because of that direct experience

- Being the community – they are, synechedochically, the community: they are the voice of the community, the community is embodied in them.

However, at other times, they identify themselves as being quite distinct and separate from the community, again in three primary identities:-

- Serving the community – their job is to represent the views etc of the community, which they can through procedurally fair and extensive consultation: it is not their role to make decisions, merely to put realistic options before the community, in whose hands the final decisions will lie

- Leading the community – the community is seen as a distinct entity that needs to be ‘taken with them’ as they, the NP group as a distinct entity, decide which proposals to put forward and how

- Challenging the community – broad generalisations can be made about what “the community” will want, think, or accept, that the NP group will have to or would like to challenge – eg with new solutions to longstanding problems, or over the inevitability of accepting existing local authority land allocations

Each of these identities also of course implies an identity or several being constructed for the wider community and sometimes also for other actors, eg the local authority. There is no inherent problem in a group inhabiting different identities; indeed, it would be unusual if they did not. Rather, it is a useful reminder that the relationships between these groups and the wider community is not simple or straightforward, and that these complexities need to be taken into account when considering the forms of organisation and communication that might lead to the most fruitful co-production of knowledge, where these groups form the intersection between ‘community knowledge’ on the one hand and ‘technical knowledge’ (from consultants, local authorities, existing evidence documents etc) on the other. The risk, as highlighted by Elena Besussi, is that existing institutional forms and structures may be enforced through some of these identities in ways that are not conducive to that co-production.

Information

Ok, so this is actually more about knowledge than information, but I like alliteration! The final speaker, Yasminah Beebeejaun, emphasised that challenging dominant assumptions about knowledge is an integral element of co-producing knowledge at neighbourhood level: for example challenging the notions that ‘community knowledge’ is in some way inferior to ‘technical knowledge’ produced by experts, or that ‘community knowledge’ is somehow just out there, waiting to be easily gathered. She called for a more expansive understanding of planning, one that was better able to incorporate the knowledge and values arising from lived experience while not losing sight of the need for the technical aspects.

Neighbourhood planning may, as many speakers emphasised, offer a space for new, creative, innovative and improvised ways of building and organising knowledge by and for communities, with the potential for enacting just such a more expansive mode of planning. But there remains the risk that this possibility will be foreclosed if NP groups internalise and reproduce existing ways of knowing and evidence-gathering. Certainly, the groups that I am working with feel somewhat bound and constrained to produce evidence that gets its legitimacy from fields of experience other than neighbourhood planning – local planning, development management, surveying etc – limiting their ability to improvise and be creative. There is a perceived need to quantify and measure, rather than to develop a more qualitative, richly descriptive type of evidence that I think many expected of the ‘community knowledge’ dimension of neighbourhood planning. The point is, the belief that only ‘technical’, quantitative knowledge will be accepted as ‘real’ evidence tends to lead to the reproduction of existing norms and forms and runs the risk of stifling the potential creativity and new ways of working that would underpin genuine neighbourhood co-production of knowledge.

Inversions

A number of speakers and other participants raised inversions, and these are the sorts of practices that may be needed in order to give neighbourhood planning the best chance of embracing new ways of doing things. These included:

- Andy Inch (Sheffield University), the first speaker of the afternoon, talking about planning and research as being ‘hard to reach’ by many members of the community, rather than us thinking about those members of the community as being ‘hard to reach’ by planners or researchers. Inverting the way we think about this might lead to new ways of thinking about how to tackle the problem and bridge the gap

- Prof Nick Bailey (University of Westminster, Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Forum) talked, amongst other things, about the importance of stakeholder engagement, referring to bodies such as the local authority and Transport for London. Stakeholder engagement is usually a process by which relatively more ‘central’ and powerful bodies ‘go out’ to seek the views of relatively more peripheral and less powerful bodies or individuals. The very process of undertaking stakeholder engagement in these terms may help to foster identities of NP groups and their communities as being empowered.

- Prof Simin Davoudi (Newcastle University) made a comment from the audience about the need to see people’s capacity to engage with neighbourhood planning not from established perspectives and on the basis of the ‘terms of engagement’ that we tend to favour and are accustomed to, but rather that if communities themselves (in all their heterogeneity!) are able to decide on the terms of engagement, their capacity – and willingness – to engage may likewise be transformed

If we are to achieve a more expansive form of planning, one in which communities in all their multiple, complex and shifting identities are genuinely able to co-produce knowledge rather than being co-opted into current modes of planning, albeit on a smaller scale, then perhaps it is inversions of the current system like these that need to be considered more seriously. Neighbourhood planning offers promise for co-production of knowledge, but we must be aware of the risks of reproducing existing ways of doing things that will tend to restrict its scope for doing so.

Think you’ve done a good job of covering a number of the potential drawbacks to neighbourhood planning here. Such a good job I might even conclude you are slowly being turned off them as an efficacious vehicle for truly local decision making in the planning system!

Tony

LikeLike