Our first blog from our third event comes from Jocelyn Cunningham who is an Associate of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), running the Arts and Social Change programme in People Shaped Localism, a partnership with Wiltshire Council. Following her work as Director of Arts at the RSA, Jocelyn founded Other Ways of Working, which acts as a creative intermediary across sectors. Her thinking can be found in the RSA paper, Knitting Together Arts and Social Change and recent case studies in cultural education.

Gathering Creatively

I had the fortunate opportunity of spending a day reflecting on creativity and community development at an event in Sheffield hosted by the ESRC as part of the Connected Communities programme and the Department of Communities and Local Government, entitled Ways of Knowing in Neighbourhood Working; Policy vs Zine. Refreshingly including policy-makers, academics, artists and community activists, the event asked the question: What kind of policy initiative would encourage new kinds of community development?

I have spent some time pondering the relationship between stuff that happens on the ground that really works for people, particularly of the creative variety and policy-making and the inherent challenges of any initiatives that seek to empower and strengthen community cohesion, integration, belonging, well, you name it. There are two areas I’d like to reflect on from this event: the divisive ways we perceive and refer to communities and the possibilities of creative practice to address this.

Ways of Working explored a rich array of perspectives on these overused and commonly conflated terms: community, collaboration, co-production, even creativity. Throughout the day, we all felt the need to clarify these terms, unpick what we meant by ‘challenging’ or specify who we mean by ‘young people’ for example, and reframe our reference points in discussions. Invariably we returned to considering the conditions essential for positive community development and effective policy-making.

Community as a porous, complex and ever-changing thing

Recently, I wrote a blog for the RSA on the urgent need to shift our conception of what ‘local’ means and avoid reducing this notion to people bounded by socio-economic background, geographic boundaries or by the characteristics of ethnic background, age or faith. The complexity of who is encompassed by this term ‘community’ tends to be managed through two unhelpful and simplistic frames:

1/ we perceive places as characterised by discrete communities or worse, a set of needs and problems to be solved rather than an ever-changing web of relationships that continually evolve within any definition of community, including communities of interest or practice. Initiatives target specific groups of people based upon deficit concepts, on perceived or actual needs and miss the opportunities of seeing people as assets within a web of relationships.

2/ we see communities and who ever ‘we’ are as separate entities. People in communities are somehow ‘other’ and a divisive ‘us and them’ mindset becomes the normative way of conceiving each other and initiatives or projects. Any position of influence and power, from elected member to policy-maker to academic to someone leading an initiative, is inevitably perceived as separate to the community of people they are working with. A council or public service also holds a myriad number of communities within them but are usually held as responsible for financial decision-making that exacerbates the ‘us and them’ mindset that in turn, creates the culture of complaint and defence. This naturally discourages anyone in a role of decision-making to take part in open discussions or activity that encourages vulnerability such as creative practices.

I appreciate that taking into account the complexities of belonging, identity and what binds people together or keeps us distinct means that policy-making or problem-solving tends to simplify in order to help make something happen. It’s easier. If we agree that positive change lies in strengthening the social fabric of a place, then this cannot be about work with targeted groups of people and must shift to an ‘us’ mindset. We need to uncover, value and work with complexity and challenge simplistic perceptions of identity, belonging and so-called representational communities.

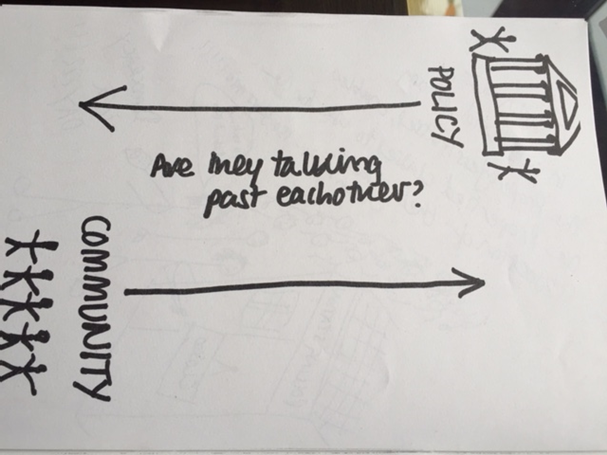

Time and again at the event, the rich nuances of what we mean by community were revealed in fascinating ways. Professor Mihaela Keleman spoke of her research with Japanese communities after the tsunami and their perception of volunteering: ‘We don’t volunteer in our community. We are the community.’ This turns the notion of volunteer and community on its head. Mariam Shah spoke of the urgent need to stop regarding individuals as representative of their communities, as community spokespersons. Hugh Kelly showed his films that continually revealed how the simplistic defining of community problems that failed to value what was already present was, at best, ineffective and at worst, destructive. The thread of ‘what is already present’ wove through most discussions and presentations. I was particularly touched by the sadly familiar theme of how the cultural bastions of culture (such as Sage Gateshead and the like) can be perceived as holding and representing culture whilst the everyday culture of the people in communities surrounding such iconic buildings can feel as if their culture has been usurped or appropriated. Too often, cultural institutions work in the area of ‘community outreach’, which serves to exacerbate such perceptions. Words like trust or the recognition of the time needed to build meaningful relationships surfaced throughout the day. But how do these ephemeral and long-term conditions feed into policy development?

Images from the zine the event created

The RSA has been considering lately what it would mean for policy makers or public services to be part of collaborative communities, not as separate from them. Gillian Tett’s new book, The Silo Effect examines how silos and fragmentation are at the core of our global economic crisis and stresses the need to pay attention to the cultural and organisational patterns that shape our behaviour. What would it take to develop culture change so that collaboration across services, across communities and hierarchies, across differences in perspectives might be real? My response to this question is to build upon the existing work from across the socially engaged creative sector and learn from the principles and conditions necessary for good creative work that crosses traditional boundaries between people.

Creative activity can influence systemic thinking. Cultural historian, Robert Hewison identified the singular importance of the role of creativity in thinking about how systems work at a conference late last year: ‘It is the reconfiguration of relationships that gives a system its essential characteristics…Creativity comes from being at a point of exchange.’ Creative activities were a refreshingly intrinsic part of this event, indeed as they should be for something entitled Ways of Knowing. Too often these are used as warm-up or team-building activities that are not a direct part of the knowledge sharing of the day. As a group, we responded to these ideas through creative exercises designed to develop our own conversations about communities (with a rich array of buttons) and created a zine as a record of our thoughts. Importantly, many participants unpicked the inherent value of this approach in fostering a different and more open kind of conversation. Mihaela Kelemen spoke of how arts based practices can discourage hierarchies and help participants uncover and articulate complex ideas through alternate ways of relating to each other. Malaika Cunningham spoke of her research with the Crick Centre on the relationship between participating in arts based activity and informal political engagement. Frequently, the importance of values, imagination and the recognition of what people already had to offer (as opposed to deficit models) were raised.

Creative Gatherings

I spoke a little about my approaches with Creative Gatherings that myself and others have developed, beginning with Creative Partnerships, then with the RSA in Citizen Power Peterborough. The principles of such gatherings are very similar to the conditions that we discussed at the event – neutral spaces so that a single agenda does not dominate, real attention to who is in the room and who is not and the critical importance of imaginative activity to unlock new ways of working together. As the case study on this approach reveals, they are purposeful but that very purpose is developed by those taking part. I cannot stress enough the importance of doing creative activity together to help reframe participants’ agendas. My experience has always revealed that this encourages people to see each other differently which in turn, develops alternate social action. In the panel discussion, Mike Fitter of the Sheffield Faith Leaders group drew a diagram that tried to encapsulate much of the discussion. This positioned the ‘safe’ space for community dialogue at the centre of all the intentions, conditions and activities that we valued at this event, such as mobilising dissent and solidarity, co-production, learning, mediation, arts based activity and a sense of agency. However, it is crucial to perceive this safe space in the middle as porous and continually open to a freedom of movement to and from this collaborative safe space. There are many examples of creative assemblies tackling challenging subjects over time in ways that both build connections between people and make change happen. Have a look at the National Theatre of Wales’s Big Democracy Project.

So, my recommendations regarding policy creation as a reflection of the day? We must find ways of creating opportunities to break down divisions between us. It is not just silos of public services we are challenged by, but silos of thinking, perception and practices. There were useful ideas emanating from the day such as small pots of funding made freely available to community activists but this is tinkering. We know that the siloed thinking that leads to initiatives regarding places and communities struggles to have long-term impact. Public services remain fragmented and individuals and communities are isolated. We lack imagination and courage in connecting people and their ideas together. We fail to learn the ever-present finding of the singular importance of relationships over time. Bringing decision-makers and people in communities (of location, practice, interest) together in creative frameworks is a direct means of holding the space necessary for this to happen. No more us and them. It has to be about us and having the courage to do things differently.