THINK LOCAL! Franziska Eckardt, CHEPS, University of Twente, Co-author: Willem-Jan Velderman, CHEPS, University of Twente

Recently, I travelled to Bristol for a ESRC Seminar “Neighbourhood Ways of Knowing and Working”. Before the start of the Seminar, I had some spare time, so I decided to go out for a little walk to discover the city. One my way, I suddenly realised that the rather grey cityscape was starting to change around me as I progressed – more and more houses with colourful painted exterior walls and catchy messages appeared. I found that the whole district – called “Stokes Croft” according to my map – seemed to talk to me (see Fig. 1).

Fig 1. Stokes Croft

Later that day at the Seminar, speakers from all over the UK presented different examples of how citizens at the neighbourhood level were starting to find ways to express their community interests and how they were addressing local institutional barriers. The seminar drew to a close with the final speaker – Chris Chalkely – entering the podium and presenting his talk about “Taking back property by using art in public” in Stokes Croft (http://www.bbc.co.uk/bristol/content/articles/2007/09/06/prsc_feature.shtml).

Returning the Netherlands, I recalled clearly one particular picture from Chris’s presentation: a man holding a sign with the words written on it “93% of local people say no to Tesco” and a big slogan “think local – no Tesco – our council must listen” (Fig. 2). This slogan reminded me of research recently performed by my CHEPS colleagues, on the subject of Waste Water Injection in North-East Twente (http://doc.utwente.nl/99513/1/R301_InDepth.pdf).

Fig 2. Boycott Tesco

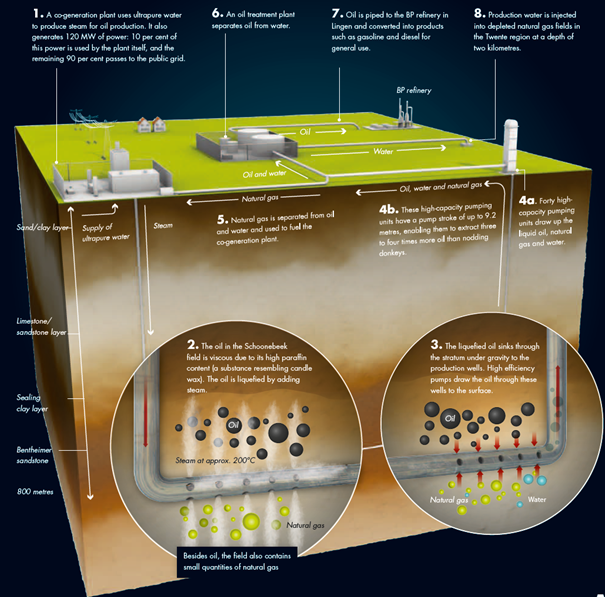

The case study discusses a controversial situation of waste water injections in the Twente region, located in the eastern Netherlands. The controversy arose when a small group of concerned citizens from north east Twente region mobilised to try to improve their direct surroundings. The reason for this was that they were worried about the local underground waste water injections in former gas fields being performed by the Dutch oil company NAM (De Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij) since the mid-2000’s. The NAM was extracting oil in the neighbouring Drenthe province using steam, in a process similar to fracking, and had come up with the wheeze to store the by-product waste water by injecting it into already exhausted gas fields in Twente (see Fig. 3).

Fig 3. Water Waste Injection in North East Twente

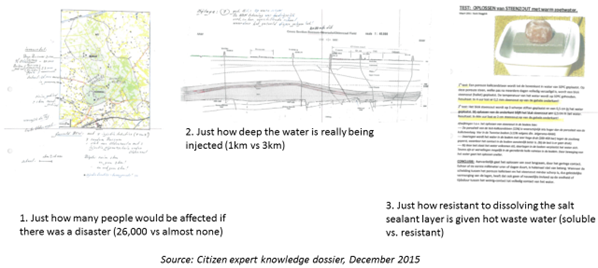

Local citizens’ concerns were related to subsidence, and the potential for earthquakes and calamitous water pollution. To contest the prevailing professional expert consensus that these activities were safe, the group of ‘smart’ citizens gathered more and more knowledge proving that their concerns about the waste water injections were legitimate (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 – The rejected citizen knowledge 3 examples

However, various political bodies neglected citizens’ concerns and the evidence they presented, on the grounds that citizens’ knowledge could not be regarded as formal expert knowledge. It took a public TV reportage by the provincial broadcaster (RTV Oost) in December 2014, for citizens and the waste water injection case to really receive the firm attention of local politicians and experts. An increasing amount of expert-research as well as empirical findings confirmed citizens’ concerns that the waste-water injections seemed to be less safe than the scenarios previously promoted by the NAM (e.g. waste water bacteria seriously corroded the pipelines in the ground necessitating an emergency halt to pumping still in force today). From that moment the issue became politically highly sensitive, with local, provincial and national governmental bodies all attempting in their own way to address this issue by setting it on the policy agenda.

Both the Dutch waste-water injection case as well as the Stokes Croft street art activities are both situations where local (smart) residents took matters into their own hands. Whether by drawing art or gathering a citizens’ knowledge dossier, in both cases citizens found their way to raise their voices and express their community interests. In the waste-water injection case, local residents were able to become local experts who can be helpful in revealing – and potentially therefore solving – local and regional problems. Making better use of this “smart citizen” knowledge could potentially be extremely useful for local authorities to improve the overall quality of local decision making. In conclusion, we would like to return to the picture mentioned at the beginning of this post – “think local – the council must listen” as it chimes perfectly with our wider message: local authorities need to consider much more systematically the ways they can listen to the voices of their citizens and receive their signals which can contribute to developing well informed policy-solutions to these problems.

Acknowledgment

Many thanks to Antonia Layard and the Economic and Social Research Council for their invitation to attend the workshop and to write this Blog post. We would also like to thank the Institute of Innovation and Governance Studies at the University of Twente for their support in this project, and all interviewees who gave their time in our research. Paul Benneworth helped us with the text layout and proofing. Any errors or omissions remain the responsibilities of the authors.

Community Buildings, Heating and Spaces: The Importance of the ‘Local Community’ at a National Level? – Edward Burtonshaw-Gunn, University of Bristol

From a small room in the Wills Memorial Building at the University of Bristol, 40 people – academics, community housing leaders, and employees of the Department for Communities and Local Government – took a tour of community projects across the UK and parts of the world. Through the portal of fantastically communicated presentations, we witnessed an insight into all things community housing, community energy, and community space.

As part of the ESRC-funded Ways of Neighbourhood Knowing and Working seminar series, this session invited speakers from across academia and local communities to present and discuss community housing, energy, and spaces.

The day began with a scene setting introduction from Robert Rutherfoord (DCLG) providing an insight into one of the most utilised forms of community involvement in local housing, Neighbourhood Planning. Introduced through the Localism Act 2011, neighbourhood planning provides communities with a voice to shape their local area. The success of neighbourhood planning, Robert says, is evident through the fact that 20% of the population are now covered by a neighbourhood plan area.

This evidently highlights the desires for community input into housing, which led neatly onto our first set of presentations into Community Housing which focused on Community Land Trusts. CLTs are non-profit organisations which generate a genuine ground-up approach to permanently affordable housing for the local community.

It is here where we started our tour of the UK, with a presentation by Matt Thompson into Liverpool’s CLT network and the progression of today’s CLTs from the 1960s Shelter Neighbourhood Action Projects. Liverpool has been the city to lead nationally in forms of public sectors homes built with residents, aiming to rehouse the city’s most needed, with fair rents, without displacement to the urban periphery. A point of great interest from Matt’s presentation was home the community initiatives that began in the 1960/70s paved the way, institutionally and spatially, for the modern successes of CLTs. Exemplifying that while CLTs are a modern initiative of community housing, the fundamental idea is built on prior experiences and hard work.

Liverpool CLT was a popular topic of the day, with two more speakers – Marianne Heaslip and Michael Simon – providing discussions on CLTs within Liverpool. Marianne delivered an insight into the opportunities and difficulties facing CLTs; some of which were unexpected. Land value is crucial to CLTs, while complaints in Southern England revolve around the land value being too high, posing questions of affordability for CLTs; Marianne informs us that in parts of Liverpool, the land value is in fact too low to be able to borrow a financial investment against. Concerning knowledge, but very important to share with promoters of the community housing cause. Finally from Liverpool, Michael shares his insights as Community Development Co-Ordinator for a Liverpool CLT, Granby 4 Streets. While he recognises that CLTs are a small means of housing production within the city, he maintains their importance through the Local Authority’s desire to keep homes in the local community, for the local community.

Our tour of community projects in England and abroad

Next, Tom Moore took us across the South-West of England to present to us his research with CLTs in Devon, Dorset and Somerset. Some fantastic insights into the motivations of the local community involvement with CLTs. Whether to provide a localised response to the Housing Crisis, the moral value of community land, or to provide some weight in localised involved in new build decision-making; Tom’s presentation provided a wonderful insight into them all.

Staying in the South-West, but shifting focus onto the greatest city across the UK, Bristol. Keith Cowling is the chair of Bristol Community Land Trust, who commenced his presentation with a celebration of their first site completion as an organisation – so a huge congratulations to them!! 325 Fishponds Road is the first CLT build in Bristol, creating 12 homes from a conversation of an old Victoria school room, and newly built three bedroom houses.

While land values in part of Liverpool may be deteriorating, Bristol is currently overheating; with the 3rd largest house pricing growth nationally, behind only London and Cambridge, respectively. It is the financially impact of high land values which impede affordable housing within the city; without funding, initiatives and organisations such as Bristol CLT struggle to compete within commercially driven markets.

Martin Field, Senior Researcher at the University of Northampton, offered his insights and expertise into alternative forms of community led housing to the so far, much discussed, CLTs; the motivations behind community lead housing; and most importantly, joining these two silos of knowledge together. Whether community housing initiatives take the form of communes, eco-villages, or self-build projects, their ability to provide affordable housing for local people is a key motivation.

Yet the list is extensive, as it also provides potential renovation of previously derelict property, the foundations to build neighbourhoods producing a new dynamic, or purposefully creating communities based on values of sharing and communal space. Ultimately, Martin says, community aspirations are as good – if not better – than commercial led developments, as they are the objectives of the community.

Our next presentation took us to Oxford, with CLT development director, community housing led for a design collective, and PhD student, Charlie Fisher. Charlie presented us with some of the community-led housing opportunities currently undergoing in Oxford, a city with a dire land value problem and other obstacles preventing sustainable growth. His experiences leads him to understand that community land projects progress at a snail pace compared to commercial developments due to the lack of professional expertise and often numerous organisations involved, and as a result, the objective to provide affordable rents, even when capped at 80%, is fundamentally difficulty as the land values are increasing dramatically over time.

The first of our international perspectives, and the last in our housing topic, brought us to Austria, to the cities of Vienna & Salzburg, by Richard Lang of the University of Birmingham. A greatly positive atmosphere from our Austrian cousins where the co-operative housing sector is well established through central government policies influencing provincial government policies and ultimately providing large cooperatives and housing associations with the means to build. To provide an insight into the discussion, Richard cites Vienna as promoting the self-build model through residents co-initiating, co-planning, and co-constructing projects. Through the municipality providing inexpensive sites to not-for-profit housing developers, competition between developers measures proposals identity, community building, social mix and tenant participation; factors which all promote the values of community housing.

With our interest of the community now shifted towards community energy, Jelte Harnmeijer discussed the fascinating approaches of decentralised energy with reference to the successes of similar schemes in Denmark and Germany. His interests lie in the use of various forms of community renewable energy, schemes which has seen increased popularity with 30% growth year on year since the financial crisis of 2007. Specifically, his research into the use of geothermal minewater energy in Scotland utilises empty mineshafts to heat millions of litres of water – and for those without a Ph.D in Geosciences, Jelte says, this does not mean warm minewater will come through your taps! Ultimately, these alternative approaches to providing community energy, of which geothermal minewater is just one, are technically and economically viable for communities to invest in and benefit greatly from; as demonstrated through energy comparisons with Denmark and Germany, two countries which already apply these approaches and realise the rewards.

Next, Ruth Bush of the University of Leeds discussed the benefits of District Heating, a sustainable energy system of distributing heat generated centrally to local residents and commercial spaces. From Ruth’s presentation, the benefits of such systems are extensive: increased energy efficiency, increasing environmental benefits, and a form of generating local income. But Ruth questions whether local communities possess the ability to implement a transition to community district heating. As district heating meets resistance across its proposed implementation, primarily from existing actors or institutions, the success for potential district heating is dependent on a radical transition through regulation and development of political and policy-based debates focusing on the numerous benefits.

The final international perspective of the day took us to Japan, Lorayne Woodend discussed the traditional and still greatly important role of community buildings in the Far East country. Machizukuri is a broad Japanese concept equating to a community building, includes a wide range of activities such a community planning and social movements and bares similarity to localism and neighbourhood planning the UK. Her research explored different forms of buildings from the reuse of vacant spaces revised for the benefit of the local community as multifunctional spaces, to purpose built outlets for a place for local producers to retail produce. While these examples are specific outcomes of community buildings, they highlight the importance in rethinking, revaluing, and reusing community spaces for greater community benefit.

Returning to the UK to a fantastic initiative of Playing Out. Naomi Fuller presented the simple idea of retuning residential streets to the historically public spaces they used to be. While residential streets are primarily carparks and are ultimately an underused resource, playing out promotes street closures to allow children to play out in the streets; encouraging social community interaction for both children and adults, healthy exercise in an otherwise vacant urban environment, and creating more liveable and pleasant communities. While the scheme has been successful in achieving these benefits in 350 streets, it is restricted by barriers of legality, social hierarchy and conformity.

Moving back to the wonderful City of Bristol, Chris Chalkley of the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft gave a powerful and demonstrative presentation on the power of organised community in creating space. Stokes Croft, an area of vast cultural diversity, has been largely financially neglected in the past and as such, has developed uniquely to the rest of the city. It embraces this unique factor to improve the local community through local efforts. Chris’ presentation captured this essence perfectly by demonstrating some of the impactful work volunteers have done to safeguard the character and opportunity of the area of the city.

Our final presentation of the day, before a well-earned trip to the pub, featured a presentation by Nicola Hazell of Groundwork, a not for profit organisation working with local communities to improve the quality of life. Nicola emphasised that communities are at the heart of what the organisation aims to achieve through creating and managing open green spaces, delivering a range of training and employment programmes, and education in environmental programmes to encourage a reduction in waste and saving money.

Highlighted in the final session of the day is the common obstacle to a whole range of community schemes discussed throughout the day, and that is the financial aspect. There are numerous and varied forms of community initiatives which bring a whole host of benefits to the people, but these schemes are constantly and consistently hamstrung by the financial burden; and, in a time of austerity, this barrier seems like an immovable object.

So what can a room of academics, community housing leaders, and employees of the Department for Communities and Local Government do to champion the necessity of community focused initiatives? How can the importance of ‘local community’ be transferrable to a national scale? If financial backing is the primary barrier to success, what – or more likely, who – can make a difference?

These are the questions that surround the success of local community schemes, and their answers are hard to come by. But if there is only one thing to take from the day, then remember that we are not alone in striving to achieve more, this network of advocates is ever increasing, and at some point, it must become too big to ignore.